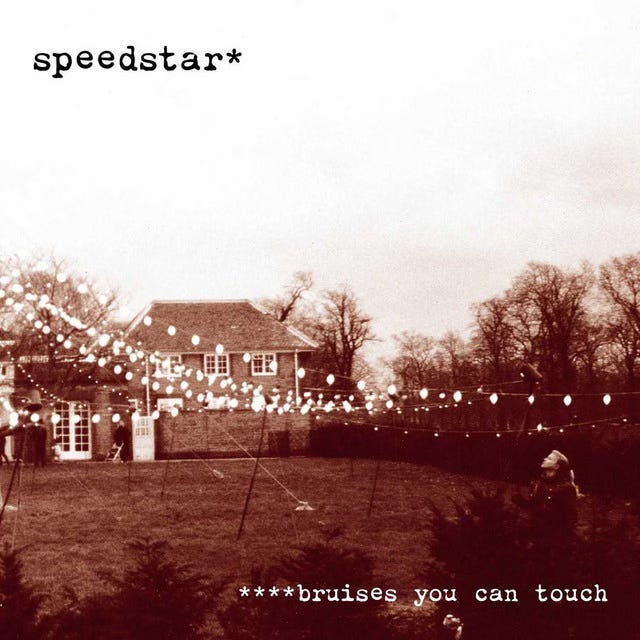

This week’s pick is from Jason Pan of the DMO Union. He’s brought us gold before—now he’s submitting Speedstar’s Bruises You Can Touch, a 2002 Australian gem that somehow never left the country. Ready to shape the next episode? Join the DMO Union and vote on which album we dig out next.

Remember 2002?

Not the year itself—that’s easy. The towers had just fallen. American Idol was new. We were burning CDs at college and pretending Napster wasn’t about to blow everything up. But do you remember what 2002 sounded like? Because there was this moment, this brief window after Britpop imploded and before emo went nuclear, when rock bands figured out you didn’t need to scream to make someone feel something.

Speedstar lived in that moment. And then they vanished.

The Sound of Almost

Bruises You Can Touch dropped in May 2002 on EMI Australia. Number 81 on the Australian charts. Two singles that barely cracked the top 200. And then… nothing. No UK release. No American push. Just five guys from Brisbane—Alistair Bell, Richard Johnston, Dave Love, Ben Smith, and Luke Sullivan—making an album that should’ve been everywhere, relegated to the import bin at Virgin Megastore if you even knew where to look.

Here’s what’s wild: this wasn’t some weird, unmarketable art project. This was exactly what was working in 2002. Travis had just done The Invisible Band. Coldplay’s Parachutes was still in rotation. Starsailor, Keane, Snow Patrol—all these bands were building careers on the same blueprint Speedstar was using. Spacious arrangements. Falsetto vocals that cued tension and release. Bass lines doing the heavy lifting while guitars painted emotion in broad, fuzzy strokes.

So why didn’t anyone outside Australia hear it?

Listen to “Revolution”—the lead single—and try to tell me this wouldn’t have fit perfectly on KROQ in 2002. That fuzzy bass line drives the whole thing, letting the vocal sit right on top where it needs to be. The guitars? They’re patient. They wait. And when they finally come in with that fizzy, amp-driven distortion, it doesn’t feel like a trick. It feels earned.

“Revolution… there’s this fuzzy bass line kind of driving the melody through the whole thing, and it lets the vocals sit on top and really draw you in and then the guitars can then kind of move in and out as needed.”

“Crazy Happy” does the same thing, building this jazzy drum feel—very Radiohead, very OK Computer-aftermath—until it crescendos into something that feels both intimate and huge. The whole album works like this: lull you in with sweetness, then hit you with moments of controlled chaos. Forty minutes of tension and release, over and over, and somehow it never gets old.

What Worked (And What Didn’t)

The production on Bruises You Can Touch is deceptively simple. Producer Steve James gave them room to breathe—none of that late-90s Britpop overproduction that killed Be Here Now and made Think Tank feel bloated. Instead, you get space. Actual silence between the notes. When the guitars distort, it’s raw and unpredictable, like a Fender amp pushed just past its breaking point. That tone has movement to it, a fizzle that adds excitement without relying on compression or studio tricks.

“It sounds like to me, like an amp you know, overdrive, maybe like a Fender, and it has a lot of movement to it. Like when they’re really laying in the guitars and letting them distort and be a little noisier, it has like this fizzle to it. It creates a lot of excitement without playing a ton.”

But there’s a tension in the record that never quite gets resolved. The falsetto vocals—used effectively to shift mood and trigger release sections—can feel predictable by the halfway point. You know when the big emotional moment is coming. You know the formula. And while that formula is genuinely satisfying the first few times, repeat listens start to reveal its limitations.

The Ones That Got Away

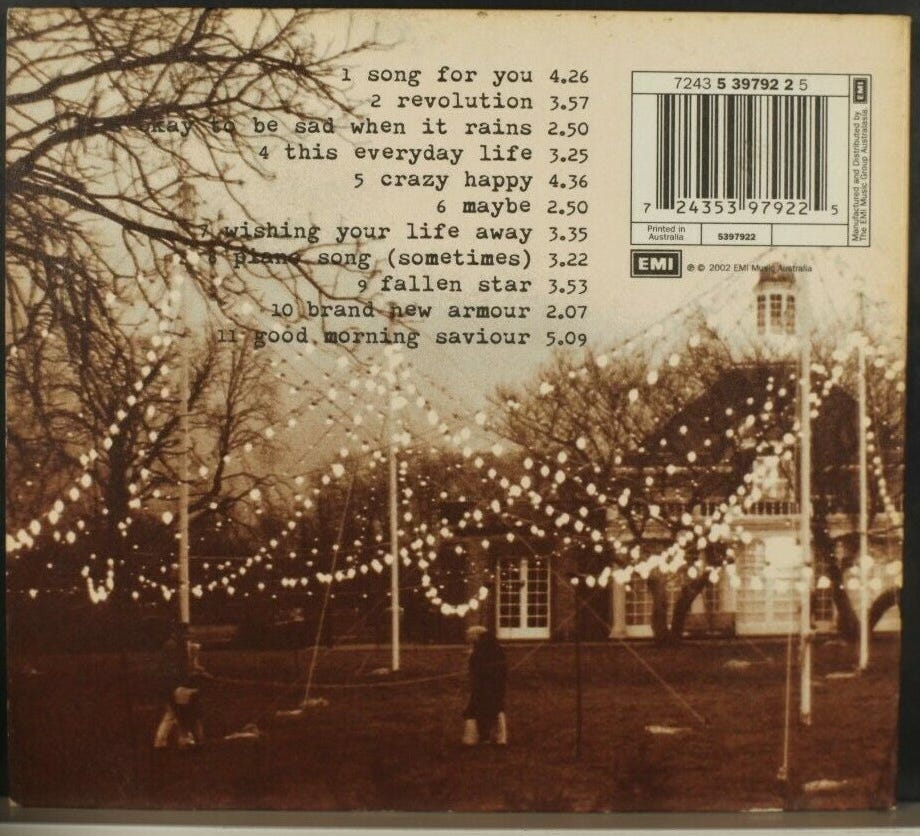

There are hints everywhere of what might’ve been. The Hammond organ that opens the album? Gorgeous. But it barely shows up again. The female harmonies on “It’s Okay to Be Sad When It Rains”? Beautiful. But it’s just one song. The cello on “Fallen Star”? Yes, more of that, please. Even “Piano Song,” which strips away the guitars entirely and leans into sparse melody and room-tone production, proves Speedstar could’ve pushed into weirder territory—more shoegaze, more piano, more strings—if they’d wanted to.

“I wish there were a couple more moments like piano song because where it steps out of the formula a little bit more clearly. I found myself get my brain thinking getting a little accustomed to it by halfway through the record.”

This is an album that almost takes risks. It almost leans into the atmospheric weirdness of Radiohead. It almost goes full piano-pop like Keane. It almost gets as raw and emotional as Damien Rice. But it stays in this comfortable middle zone—spacious post-Britpop with big crescendos—and while that’s not a bad place to be, it’s also not quite enough to stand out in a crowded field.

What’s striking is that Speedstar seemed to understand the fundamentals. They knew how to keep slow songs moving. They knew how to use dynamics. They knew how to build genuine emotional moments.

Why This Matters Now

In 2002, when everyone was chasing the next big thing, Speedstar made something patient and thoughtful. They understood that slow songs need propulsion—something driving them forward even when the tempo drops. They knew that space between the notes matters as much as the notes themselves. They built an album that works as a whole, not just as a collection of singles. Maybe that lack of an obvious radio hit is exactly why EMI didn’t push it globally. Maybe they didn’t want to compete with Coldplay and Travis. Maybe they just didn’t believe Brisbane could produce something this polished.

Or maybe—and this is the part that stings—they were right. Because even with everything going for it, Bruises You Can Touch didn’t break through. Speedstar released one more album in 2004 (Forget the Sun, Just Hold On, which reached number 59), then called it quits in 2006. Their MySpace page is still up, top eight blank, frozen in time.

Twenty-three years later, we’re finally catching up.

What do you think? Would Speedstar have made it in the US and UK with the right push, or were they always destined to be a cult favorite? And what other forgotten 2002 albums deserve a second look?

Songs in this Episode

Intro - Song For You

9:24 - Crazy Happy

16:39 - This Everyday Life (Into Your Arms)

22:59 - Piano Song (Sometimes)

26:09 - Wishing Your Life Away

29:12 - It’s Ok To Be Sad When It Rains

Outro - Revolution