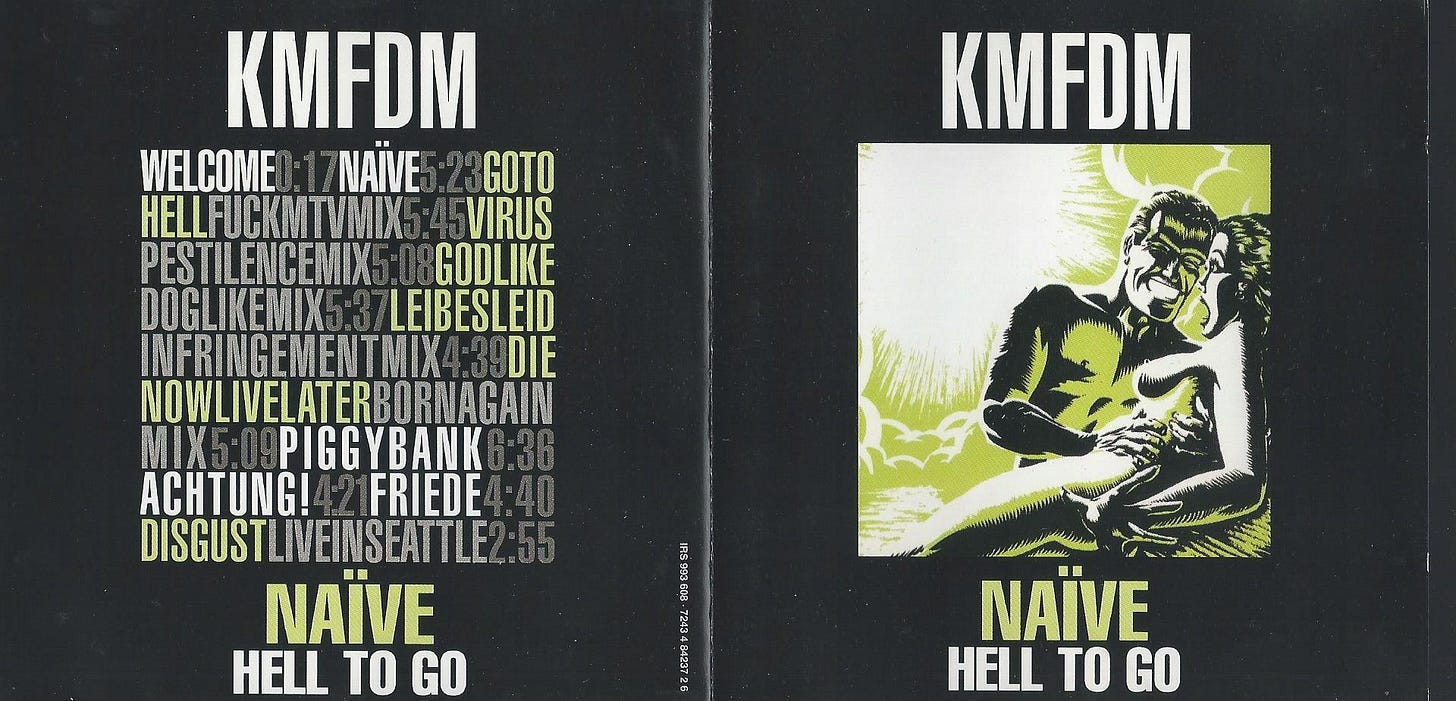

Returning Board of Directors member Ian McIver brings us KMFDM’s 1994 release Naïve/Hell to Go—a re-recorded, remixed, and reshuffled version of the band’s 1990 classic Naïve. Ian dug through KMFDM’s entire catalog (even consulted his best friend for a second opinion) before landing on this peculiar artifact: an album that was born, killed by a copyright dispute, then stitched back together and given a second life. If you’ve got an album you think deserves the Dig Me Out treatment, suggest it and join the conversation.

An Art Project That Swallowed the World

Here’s a sentence that shouldn’t make sense: a German performance art project from 1984 became the second-biggest industrial band of the 1990s.

But that’s exactly what happened. Sascha Kegel Konietzko launched KMFDM as a one-off noise piece for a gallery show in Paris. He went home to Hamburg, linked up with En Esch and a young Brit named Raymond Watts—yes, that Raymond Watts, the man behind Pig—and something clicked. Or maybe something broke. Either way, what came out of that collision was louder, weirder, and more fun than anyone involved probably expected.

The name itself tells you everything about the band’s relationship with seriousness. Kein Mitleid für die Mehrheit—“No Pity for the Majority”—was assembled from newspaper clippings on a table. It isn’t even proper German. The literal translation flips to “No Majority for the Pity,” which sounds like a Dadaist fortune cookie. When Watts couldn’t pronounce it, they shortened it to four letters, and American fans immediately started filling in the blanks. The winner, by popular consensus? Kill Motherfucking Depeche Mode. Other contenders included Kylie Minogue Fans Don’t Masturbate and the somehow darker Kill Mommy for Drug Money.

The real meaning hardly mattered. The initials became a brand. And the brand had teeth.

Wax Trax! and the Chicago Connection

By 1989, KMFDM had crossed the Atlantic to open for Ministry, and everything accelerated. Sascha and En Esch relocated to the States. They signed to Wax Trax! Records—the legendary Chicago label that was doing for industrial music what Chess Records did for the blues. It was the nerve center of American industrial: Ministry, Front 242, My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult, Front Line Assembly, Pigface. And somehow, despite being a German band on a label that warehoused the entire scene, KMFDM was the only German act on the roster.

Naïve was their first album for Wax Trax!, dropped in November 1990. It was also, depending on who you ask, the moment they became undeniable. Pitchfork later ranked it number ten on their list of the 33 best industrial albums of all time. AllMusic’s Ned Raggett called it “one of industrial/electronic body music’s key albums” and described KMFDM as “so ridiculously good that everything they touch pretty much turns to gold.”

So naturally, it got yanked from shelves.

The Copyright Kill Shot

The seventh track, “Liebeslied,” sampled Carl Orff’s “O Fortuna” from Carmina Burana without clearance. In 1990, sampling law was still a frontier being drawn in real time. The Biz Markie lawsuit was about to redraw the boundaries. The Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique had landed a year earlier with hundreds of cleared samples—but the myth that those samples weren’t cleared persists to this day. The truth is more mundane: it just cost a lot less to license a piece of the Eagles in 1989 than it would now.

KMFDM didn’t have that luxury. The album was recalled roughly three years after release. Original copies with the orange cover became collector’s items—the kind of thing you’d find in a used CD bin at a campus record store for eight dollars if you were incredibly lucky, and for significantly more on eBay if you weren’t.

What do you do when your best album gets erased? You rebuild it.

Hell to Go: A Second Chance That Almost Worked

In 1994, with guitarist Mark Durante (Ministry’s guitar tech) now in the fold, KMFDM went back and re-recorded five of the offending tracks. They reshuffled the track order, sequencing the album for CD rather than vinyl. The result was Naïve/Hell to Go—green cover instead of orange—a record that wasn’t quite a reissue, wasn’t quite a remix album, and wasn’t quite the original. It was something stranger: a snapshot of a band at two different moments in their evolution, stitched together and somehow still flowing.

The re-recorded tracks carry the DNA of what KMFDM had become between 1990 and 1994—the Angst era, the “Drug Against War” MTV rotation era. You can hear the band tightening, the production getting more confident. But the original tracks still breathe with the raw Hamburg energy of 1990. The transition between old and new isn’t as jarring as it should be. If you’re not reading the liner notes, you might not even notice where 1990 ends and 1994 begins.

Then fate took another swing. Wax Trax! collapsed financially. TVT Records bought the catalog. TVT eventually imploded too. Naïve/Hell to Go went out of print. A 2006 reissue tried to fix things but still couldn’t clear the “O Fortuna” sample, settling for an edited “Liebeslied” and tacking the Hell to Go remixes onto the end. The specific 1994 green-cover version? Not on streaming. You want it, you’re going to Discogs.

An album that was born twice and lost twice. That’s industrial music in a nutshell.

What’s Actually on This Record

Here’s the thing about KMFDM that casual listeners get wrong: this isn’t just pounding drum machines and distorted yelling. Naïve/Hell to Go is a record of wild, improbable juxtapositions—and somehow, most of them land.

Start with the guitars. “Godlike” is built around a riff sampled from Slayer’s “Angel of Death.” Not the main riff—a secondary one, played maybe once or twice in the original song. Sascha’s philosophy about heavy metal was almost anthropological: he wasn’t a fan, but he recognized that metal guitarists occasionally produced these brilliant, throwaway riffs that deserved more than a single appearance. So he took one and looped it into the foundation of what became KMFDM’s signature song. The original was a spoken-word piece performed during the Ministry The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste tour before it was reworked into the beast we know.

“Go to Hell” lifts a riff adjacent to Metallica’s “Metal Militia”—re-performed rather than sampled—and wraps it in a drum pattern that feels like glam rock. There’s a Gary Glitter “Rock and Roll Part 2” swagger buried in there. “Virus” pivots between synth-pop, hip-hop grooves, and something that sounds like ’90s Helmet. “Die Now – Live Later” drops in a drum sound so aggressively ’80s digital that it evokes Janet Jackson or Paula Abdul, set against industrial aggression. It shouldn’t work. It absolutely does.

And then there are the vocals. Sascha’s delivery is a whisper-yell—a flat, grunting, almost spoken-word bark that operates more like percussion than melody. But the record doesn’t live on his voice alone. Christine Siewert’s soulful female vocals cut through on the original tracks, creating a contrast that feels genuinely surprising. On the re-recorded “Godlike” (the aptly named “Doglike Mix”), Dorona Alberti—the daughter of a friend of Sascha’s from the Netherlands—contributes these strange, childlike vocal passages that add an eerie new dimension. Alberti would become KMFDM’s female vocalist going forward, and her soul-jazz voice brought something nobody expected from an industrial record.

The drums deserve special mention. Half live, half machine. Rudolph Naomi played real drums on the original sessions, and the combination gives the record an organic feel that most industrial albums lack. The beats aren’t just hammering at 140 BPM—there are grooves, half-time thumps, dynamic shifts. Even the programmed drums sound felt, not just sequenced.

The Brute! Factor

You can’t talk about KMFDM without talking about the art. Every album cover comes from Aidan Hughes, a.k.a. Brute!—a British illustrator whose style is equal parts Jack Kirby, Soviet Constructivist propaganda, and hardboiled pulp fiction. The angular figures, the weaponized spot color, the thick hatch lines that look like linocut prints. KMFDM’s visual identity is as recognizable as their sound, maybe more so. Hughes has been collaborating with the band for over three decades, and his “Drug Against War” video animation was the thing that pulled countless fans into the orbit in the first place.

The covers alone make you want to pick up the album. That’s no small thing in a genre where visual identity can mean the difference between curiosity and invisibility.

The Family Tree (It’s More Like a Tangled Vine)

Industrial music in the ’90s operated like a small, incestuous community where everybody played in everybody else’s band. Raymond Watts was in KMFDM before he was Pig. En Esch ended up in Pigface. Bill Rieflin played hi-hat on tracks from the original Naïve sessions—the same Rieflin who drummed for Ministry on Psalm 69 and later joined R.E.M. Mark Durante came from Ministry’s road crew. Chris Connelly from Revolting Cocks and Ministry would guest on later KMFDM albums. Ogre from Skinny Puppy showed up. Tim Sköld passed through.

It wasn’t a genre so much as a rotating cast of collaborators who happened to make brutally loud music together in various configurations. Sascha sat at the center of it all—the primary writer, the producer, the guy who kept the machine running through lineup changes, label collapses, and a mid-career breakup that produced a farewell album (Adios, 1999) that had the profoundly unfortunate timing of releasing on April 20th—the same day as the Columbine shootings. The perpetrators were fans. The band released a statement condemning the violence and clarifying their anti-fascist politics. They broke up. They reformed in 2002. They’ve been going ever since, through albums like Hau Ruck and Hyëna that circle back to some of the dub and experimental instincts of the early years.

Where Does It Land?

Naïve/Hell to Go is a record that rewards patience and punishes expectations. If you come in expecting Ministry-style relentlessness, the soul vocals and glam-rock drum patterns will throw you. If you come in expecting electronic body music, the Slayer-derived guitar riffs will catch you off guard. The first half is undeniably strong—tightly composed, full of hooks and dynamic surprises that pull you forward. The second half wanders a bit, dipping into territory that feels less focused, occasionally crossing the line from “playfully eclectic” into “a little too soft.” The album closer, “Friede,” has a wah-wah guitar thing that feels like a different band entirely.

But those first six tracks? “Naïve,” “Godlike,” “Go to Hell,” “Virus”—that run is as good as ’90s industrial gets outside of Trent Reznor’s orbit. And “Liebeslied,” even in its compromised re-recorded form (the “Infringement Mix,” aptly named), remains one of KMFDM’s finest moments—a track where Carl Orff meets machine beats and somehow nobody blinks.

The irony is that Naïve captured KMFDM at their most adventurous, drawing from Krautrock, dub, glam, metal, synth-pop, and soul in ways they’d largely abandon as the decade wore on. Later albums brought in more guest vocalists—Watts, Connelly, Sköld—and the production stayed impeccable, but the wild eclecticism of Naïve got smoothed out into something heavier and more uniform. As one longtime fan put it: the fun songs don’t have to be self-referential in-jokes. Naïve proves you can be playful without being cute about it.

KMFDM spent the ’90s as arguably the most important industrial band that wasn’t Nine Inch Nails. They were better produced than their peers, more musically ambitious, and more fun. They bridged European electronic music and American guitar aggression before that was a thing anyone had a name for. They made records that sampled Slayer and sounded like Paula Abdul in the same song and somehow made it work.

So why don’t more people know this album? Part of it is the copyright curse—the best version of Naïve has been functionally unavailable for over thirty years. Part of it is the genre’s reputation: industrial music still gets filed under “specialty” in most people’s mental record stores. And part of it is just the cruelty of timing—when your biggest crossover moment is “Juke Joint Jezebel” on the Mortal Kombat soundtrack, and your farewell album drops on the same day as a national tragedy, the narrative gets complicated in ways that have nothing to do with the music.

But the music is still there. It’s still weird. It’s still surprisingly groovy. And if you can track down the green cover, it’s still worth the dig.

For the full conversation—including Ian McIver’s deep-dive history of KMFDM, the Great Sampling Debate, and Tim’s confession that this is perfect Lego-sorting music—listen to the complete episode.

Songs in this Episode

Intro - Welcome/Naïve

19:10 - Got To Hell (Fuck MTV Mix)

24:57 - Godlike (Doglike Mix)

27:47 - Die Now Live Later (Born Again Mix)

Outro - Disgust (Live in Seattle)