There’s a particular flavor of injustice that metal fans of a certain age carry around like a badge. You know the one. It’s that moment when someone (usually someone who thinks Springsteen invented working-class authenticity) tells you that hair metal was “just dumb party music.” Never mind that you spent your formative years decoding the apocalyptic dread woven through Metallica’s riffs or contemplating mortality while Ozzy wailed about suicide solutions. Nope. According to the cultural gatekeepers, 80s metal was all hairspray and nothing upstairs.

Jesse Kavadlo gets it. Actually, he’s spent the better part of his academic career proving everyone wrong about it.

The Maryville University literature professor released Rock of Pages: The Literary Tradition of 1980s Heavy Metal in December 2025 through Bloomsbury, the same publisher behind those beloved 33 1/3 music monographs you’ve got stacked by your turntable. But unlike most academic music writing, Kavadlo’s book doesn’t approach 80s metal as a sociological curiosity or a guilty pleasure requiring apology. Instead, it does something radical: it takes the lyrics seriously. As seriously as Bob Dylan (Nobel Prize winner) or Kendrick Lamar (Pulitzer Prize winner). As seriously as Shakespeare.

Yeah, you read that right. Shakespeare.

The Metal Professor

Kavadlo’s path to writing Rock of Pages reads like a particularly honest VH1 Behind the Music episode. Brooklyn kid, played in bands through high school and college, opened for Danger Danger and Dangerous Toys at the legendary L’Amour Rock Club, graduated still not famous, got a master’s degree, still not famous, finally surrendered to academia and earned a PhD in literature. The guitar got packed away for years.

But here’s where it gets interesting. About twelve years ago, Kavadlo started playing again, this time in an 80s rock tribute band in St. Louis. And those two parallel lives (the one spent analyzing Romantic poetry and the one spent nailing the solo to “Master of Puppets”) suddenly weren’t so separate anymore. What if Def Leppard’s “Women” was doing the same literary work as John Milton’s Paradise Lost? What if Twisted Sister’s lyrics about breaking free weren’t just teenage rebellion, but actually engaged with the same themes of individual autonomy that defined Romantic poetry?

What if we’d been right all along, and everyone else just hadn’t been paying attention?

Cold War, Class Consciousness, and Coleridge

The core thesis of Rock of Pages is deceptively simple: 80s heavy metal lyrics employ the same literary devices, grapple with the same existential questions, and deserve the same critical analysis as canonized literature. But Kavadlo goes further. He argues that the music was shaped by and responded to the Cold War in ways that have been systematically erased from cultural memory.

Think about it. When critics discuss Bob Dylan, it’s always in conjunction with the social movements of the 1960s. Black Sabbath gets contextualized through Vietnam War-era paranoia. But 80s metal? It gets reduced to sex, drugs, and party anthems, as if an entire generation of musicians existed in a historical vacuum while Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev played nuclear chicken.

The evidence tells a different story. Bon Jovi’s “Runaway” video opens with a newspaper clipping about a nuclear accident. Metallica built an entire catalog around nuclear anxiety, censorship, and the military-industrial complex. Ozzy’s “Killer of Giants” explicitly addressed Cold War tensions. Even Poison’s “Nothing But A Good Time” (often dismissed as pure escapism) dedicates its verses to class consciousness: broke, working hard, hating your job, desperate for the weekend. The song literally becomes the escape it describes, but it never loses sight of what you’re escaping from.

And that escapism? Far from frivolous. Kavadlo traces a lineage from Dungeons & Dragons to Iron Maiden’s fantasy epics to Romantic poetry’s celebration of imagination. The same literary movement that reimagined Satan as a rebellious hero (thanks, Blake and Shelley) rather than pure evil found its sonic equivalent in bands singing about breaking chains, escaping asylums, and stepping through magic portals. Escapism isn’t ignoring reality. It’s human beings asserting their right to imagine something better.

Literary Devices You Didn’t Know You Knew

Here’s where Kavadlo’s dual expertise really shines. He identifies specific literary techniques embedded in metal lyrics that would make any English teacher proud, if they bothered to look.

Take Def Leppard’s “Women.” On the surface, it’s exactly what it sounds like: a song cataloging female body parts (hair, eyes, skin on skin). But Kavadlo points out it’s using synecdoche (a poetic device where a part represents the whole) while simultaneously rewriting Genesis and Paradise Lost. The video makes it even more explicit, beginning with “In the beginning, God made the land…” It’s Milton filtered through MTV, and it’s deliberate.

Metallica’s “Master of Puppets”? Straightforward personification, giving human agency to addiction. Iron Maiden’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner”? A direct adaptation of Coleridge’s Romantic poem, complete with the same themes of individual transgression and redemption.

Even Ozzy (frequently dismissed as incoherent) was doing something clever with “Suicide Solution”. The song is a pun. Solution as in “answer” and solution as in “liquid.” The suicide solution is alcohol. It’s anti-suicide, anti-alcohol, and it got condemned as pro-suicide by people who couldn’t be bothered to actually analyze the lyrics. Which brings us to…

The PMRC

September 19, 1985. The Parents Music Resource Center, led by Tipper Gore, convened a Senate hearing to address the “problem” of rock lyrics. Dee Snider of Twisted Sister was the only musician whose lyrics were targeted who actually showed up to defend himself. (Frank Zappa and John Denver testified too, but their music wasn’t on the PMRC’s “Filthy Fifteen” list.)

Kavadlo returns to this moment repeatedly throughout Rock of Pages because it crystallizes everything wrong with how 80s metal was (and still is) misunderstood. Tipper Gore claimed Twisted Sister’s “Under the Blade” was about bondage and sadomasochism. Snider calmly explained it was about his guitarist’s throat surgery. She insisted Ozzy was encouraging teen suicide. The lyrics suggested otherwise, if anyone had bothered to read them carefully.

The PMRC hearings weren’t really about protecting children. They were about adults asserting control over teenage imagination. They were about refusing to acknowledge that art is open to interpretation, and that sometimes, adults interpret things wrong. As Snider told the Senate: art’s beauty lies in its openness to interpretation. But that doesn’t mean all interpretations are equally valid. Tipper Gore’s interpretation of “Under the Blade” was simply wrong.

The hearings never engaged in actual literary analysis. They trafficked in blanket condemnations, moral panic, and the assumption that teenagers couldn’t distinguish between fantasy and reality. Kavadlo’s book is, in many ways, the close reading the PMRC refused to do.

The Bands That Were Smarter Than You Thought

Some of Kavadlo’s findings confirm what fans always suspected. Of course Steve Harris of Iron Maiden was a reader. He adapted Coleridge, referenced history, built entire songs around literary narratives. The Romantic poets valued rebellion, individualism, youth wisdom, and reimagined Satan as a revolutionary figure. That’s basically Iron Maiden’s entire aesthetic.

But other discoveries surprised even Kavadlo. Metallica, despite not projecting the bookish image of Iron Maiden, consistently engaged with big themes: nuclear war, censorship, existential dread, the cost of individual freedom. Their lyrics demonstrate “subtle intelligence” that reveals itself under sustained analysis.

And then there’s David Lee Roth. Yeah, that David Lee Roth. The guy in the striped spandex doing mid-air splits. Turns out he was writing from a working-class perspective more often than anyone noticed. “Running with the Devil” channels Robert Johnson’s blues mythology. “Jump” is deliberately ambiguous: is it about a stripper, or a suicide jumper, or a leap of faith? (Roth has claimed all three at various times.) “Hot for Teacher” frames school as a site of suppression, with kids literally in cages. And the album it appeared on? 1984. As in George Orwell. Coincidence? Maybe. But naming an album after the most famous dystopian novel of the 20th century suggests somebody in the band was thinking about surveillance, control, and the future.

Even White Lion (remembered mostly for hair and power ballads) wrote about Nelson Mandela and the Greenpeace boat sunk by French state-sponsored terrorism. They had more social conscience than most “serious” bands of the era.

The Nostalgia Trap

Here’s the paradox Kavadlo circles throughout the book: by the late 80s, metal was massively popular. MTV played it constantly. Albums went multi-platinum. Bands sold out arenas. And yet fans (then and now) identified as outsiders. How do you square that?

Part of it is that nostalgia sanitizes. When we remember the 80s now, we remember neon and freedom and pre-internet adventure. We forget the Satanic Panic, the genuine fear of nuclear annihilation, the AIDS crisis, the class divides that made Reaganomics brutal for anyone not already wealthy. We remember Steel Panther’s parody version of hair metal (an amalgamation that never quite existed) rather than the darker, weirder, more complex reality.

Kavadlo also notes that the music young people listen to as teenagers becomes their lifelong soundtrack. Neuroscience backs this up. Which means Gen X is stuck with 80s metal imprinted on our neurons, for better or worse. We can’t be objective about it. But maybe that’s okay. Maybe passionate, subjective engagement is the point.

What Heavy Metal Actually Accomplished

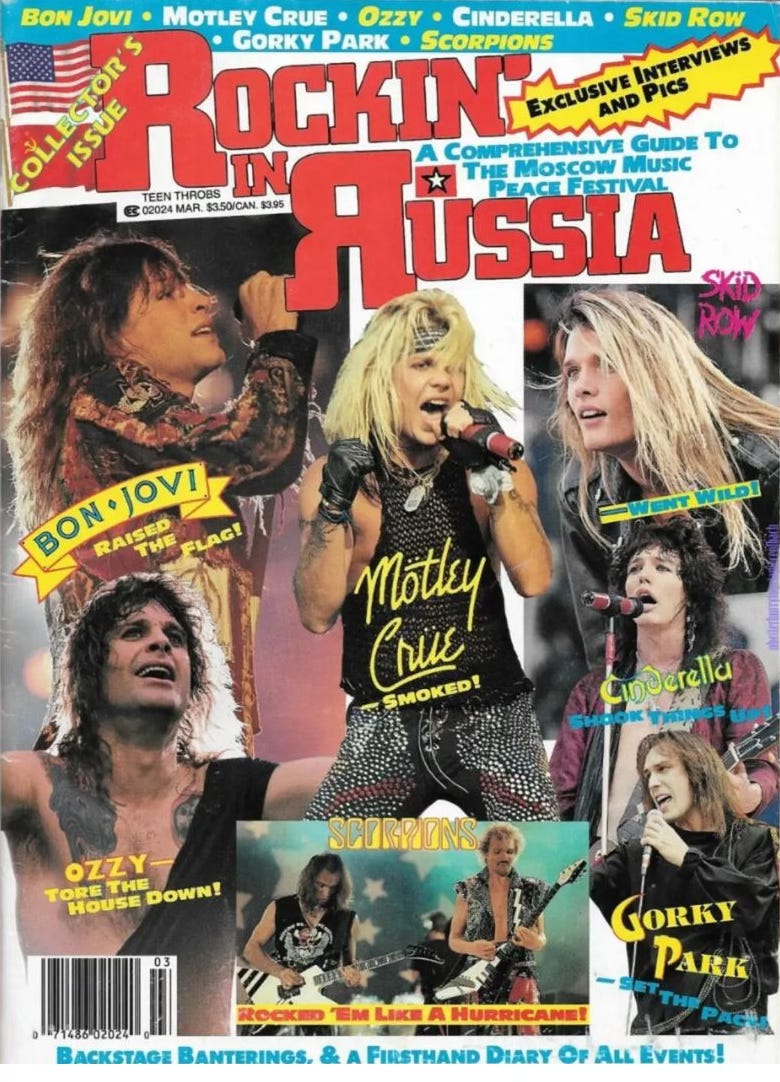

Here’s Kavadlo’s wildest claim, and he makes it carefully: heavy metal may have helped end the Cold War.

The Moscow Music Peace Festival, featuring Bon Jovi, Mötley Crüe, Ozzy Osbourne, Scorpions, and Skid Row, took place August 12-13, 1989. Over 100,000 Soviet citizens attended. It was broadcast to 59 nations. Three months later, the Berlin Wall fell.

Correlation isn’t causation, Kavadlo acknowledges. But consider: young people behind the Iron Curtain saw Western bands embodying freedom, rebellion, imagination, autonomy. They saw what was possible. And they wanted it. Ozzy’s “Killer of Giants” warned about nuclear weapons becoming the great destroyers. Turns out the killer of giants was rock and roll itself: specifically, heavy metal at a Moscow stadium showing Soviet youth a different way of being in the world.

Maybe Shakespeare wasn’t the only literature powerful enough to change history.

Rock of Pages arrives at a curious moment. The musicians who created 80s metal are in their 60s and 70s now. The fans who came of age with it are watching their own kids discover the music stripped of all context: just songs on Spotify, no album sides, no liner notes, no cultural memory of what it meant to blast Metallica while Reagan and Gorbachev negotiated arms treaties.

Kavadlo’s students (18 to 22 years old) say they “like all kinds of music”. They don’t identify tribally the way Gen X did, when the difference between Metallica and Megadeth felt like life or death. They’ve gained accessibility but lost subculture.

Which makes this book both a reclamation and a translation. For those who were there, it’s validation: you weren’t wrong to take this music seriously. The literary sophistication was real. The Cold War anxiety was real. The class consciousness was real. For younger readers discovering the music now, it’s a map to understanding not just the songs, but the world that produced them.

And maybe (just maybe) it’s a reminder that the boundaries between “high” and “low” culture have always been artificial. Shakespeare wrote lewd crowd-pleasers for groundlings who paid a penny to stand in the mud. Milton’s Satan was supposed to be a villain but became a Romantic hero. Literature has always been messier, more dangerous, more popular, and more fun than the gatekeepers want to admit.

80s heavy metal was never dumb. We were never wrong to love it.

We just had to wait for a literature professor with a guitar to prove it.

Jesse Kavadlo’s “Rock of Pages: The Literary Tradition of 1980s Heavy Metal” is available now from Bloomsbury Publishing.

Songs in this Episode

Intro - For Whom the Bell Tolls (Metallica)

11:49 - Under the Blade (Twisted Sister)

30:15 - Rainbow in the Dark (Dio)

41:24 - Suicide Solution (Ozzy Osbourne)

57:49 - Animal (Fuck Like a Beast) - W.A.S.P.

Outro - For Whom the Bell Tolls (Metallica)